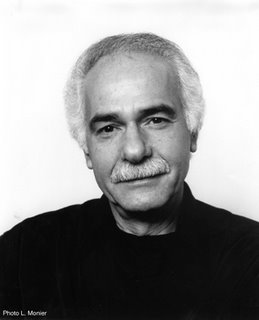

Abdellatif Laâbi - "Glory to Those Who Torture Us"

from you to meThat is a snippet of a snippet translated by Pierre Joris of a long poem, "Glory to Those Who Torture Us," by the francophone Moroccan poet Abdellatif Laâbi who lives in exile in Paris. In 1972 Laâbi was jailed and tortured for 10 years after his avant-guard literary magazine, Souffles (Breaths) aroused the attention of the authorities. This poem comes from his untranslated first volume, The Reign of Barbarism, "written between 65 and 67, before his own prison and torture experience, but prescient, knowing what was going down in the royal jails, as it still goes down in the 'democratic' jails set up by this country." (Morocco is currently one of the US' North African 'allies in the war on terror').

the truth

swear to em that you won’t believe me

we are waiting

for a wheel to break open inedible flesh

or for an eye to go out for having witnessed

no meat eater will come sew up the cesarean cuts

there’s torture

apotheosis

artifice of pogroms

fire of skeletons

glory glory

the peaceful face of the executioner

the soft hand that hacks to pieces

and the universe flows

chugging its slow train of moralities

again and again

the sweet nectar of evil

vivifying pain

skimmer of diaphragms

marble of bulbs

. . .

we are waiting

corpses or fossils

and the macabre party mounts

an ordeal without warning

they torture

and they rack what beats

and they beat what pulses

and they section what binds

crimes on the table

Laâbi is still active today, here's his website (in French). Joris has translated a more recent "Letter to Florence Aubenas", the French journalist who along with her Iraqi guide, Hussein Hanoun al-Saadi, was abducted in Iraq last year:

. . .American poet Kristen Prevellat talked to him about writing outside his native language in an interview conducted in Paris in 2001:

We think of you Florence

While hoping that an eye will open in our heart

And reveal to us

What we no longer know how to see:

Our daily gestures of small predators

That rarely don’t know themselves

The color of the lie

Spread over the whole palette of discourse

The irremediable crack in our planet

To better separate

The elected ones from the misfits

The solid web

Of the spider of indifference

That slowly encircles our faculties

The bars against which we hit our foreheads

Watching the caravan

Of our dreams go by in the distance

. . .

I don't really like the term "Francophone." Aside from the fact that it's politically charged, the term is reductive. It's a means of confining very diverse literary experiences, each of which are distinct, into a singular issue with language. . . . The question really has to do with all the writers who do not write in their mother-, or, as I prefer to call it, birth-language. Take Indo-Pakistani writers-for example, Salman Rushdie, Ondaatje, etc. In England, the writers who are currently moving literature forward are not necessarily native to England-they are people who come from outside. In France we have the example of Kundera, who decided to write in French. This is a huge phenomenon in the world today. Apart from literature that we'd call "national", there is a new kind of literature which is currently emerging in what I would call the peripheries of the world--India, Africa, or elsewhere. What is interesting here is that these literatures are straddling between two cultures, two imaginations, and two different languages. But these writers are not only "between"--they have mastered both sides. I am perfectly bi-lingual : my birth-language is Arabic, my writing language is French. Perhaps what makes what I write unique is that the two cultures are intertwined. Even when I am writing in French, my Arabic language is there. There is a musicality in Arabic, and these words enter into my French texts. I think that people are not seeing the originality of this phenomenon which is currently world wide.

[cf Juliana Spahr's talk at the end of "all languages are multilingual"]

. . .

I am not going to fight over who gets to say, "I am the one who gets to represent the French language, or that person is the one…"--that's not my problem. What is my problem? That I did not choose to write in French. Why? Because I was born in a country that was colonised by the French. In school we did not learn Arabic because we were taught in French. So when I began to write, the only language that I really knew was French. What happened after that is a very long story--of love, of hate, of rejection--with the French language. Now I am at peace with it. The colonial experience was what it was; it was tragic, but some things were brought in as well. I do not hold any grudges and am no longer enslaved, but I am a product of this history. I have only lived in France for 15 years; all that I have written in the past and continue to write today is in touch with the reality of Morocco and the Third World-- and I write in French. I am very comfortable with French, but I would not say that this language is superior over this one or that one. It's simply that I did not have the opportunity to grow up in an independent, free country where you were able to learn the language of your country in school.

. . .

Writing is still a risk in many countries. This was the case in Morocco when I was still living there--I was put in prison. In other countries, poets are assassinated. Of course, a Western poet is not exposed to the same dangers, to the same threats, but there are equally serious but different atrocities which occur in countries which we call democracies. There is the numbing of consciousness, an indifference which is gradually settling in-there are unacceptable things that happen every day, and pass as normal. How can I not be upset? I am implicated in this, because I am aware that the West is a part of me. It's my humanity as well. To me there is a single human condition, within which there are different situations.

. . .

A few years ago, for example, a young 21 year-old Moroccan was walking along the Seine. It was May Day, and there was a demonstration organized by the National Front (the extreme right party here). A few skinheads detached themselves from the demonstration. They beat this young man, and then threw him into the Seine. He died, by drowning. This particular racist crime really effected me, and I wrote a poem about it. Do I not have the right? Is poetry so sacred that it should never reflect on human tragedy, as a means of protest and denunciation? There are many racist murders, but gradually they are forgotten. I named the victim; I did not want him to be forgotten. The poet is also someone who fights for memory. If there is no memory, there is no literature (there is nothing.)

. . .

It is a poem of life that is against barbarity. Period. I'm not an alarmist, but I think that we are living in a phase of humanity that is in the process of self-destructing. We know very well what is happening to the equilibrium of the climate. The African continent is on the verge of dying, wasting away. There are countries in which two-thirds of the adults have contracted AIDS, and at the same time the multinational pharmaceutical companies refuse to sell drugs at prices which the poor can afford. Those who are aware of what's happening in the world cannot just continue to live their little lives-they must speak out.

Double Change, the bi-lingual journal where this interview appears, also published six poems from his book Poèmes périssables (2000) [Perishable Poems], translated by Max Winter:

I scan the heavens with my naked eye

and poised ear

O you

fleeing galaxies

beyond the black hole

answer me

One word from you

and I will become part

of the coming adventure

I will bury my fear

in the heavy shroud

of my shortcomings

City Lights issued a selected volume in translation in 2003, The World's Embrace, translated by Victor Reinking, Anne George, and Edris Makward, largely of work from the 90's. From "The Earth Opens and Welcomes You," dedicated to Tahar Djaout, an Algerian journalist, poet, & novelist murdered in Algiers in 1993:

. . .

The earth opens

and welcomes you

You are naked

She is even more naked than you

And you are both beautiful

in that silent embrace

where the hands know how to hold back

to avoid violence

where the soul's butterfly

turns away from this semblance of light

to go in search of its source

. . .

In two hours in the train

I go over the film of my life

two minutes per year on average

half an hour for my childhood

another for prison

Love, books, wandering

share the rest

The hand of my partner

melts little by little into mine

and her head on my shoulderis as light as a dove

On arrival I will be in my fifties

and I will have left nearly an hour

to live

and lastly, one in its original:

Du droit de t’insurger tu useras

quoi qu’il advienne

Du devoir de discerner

dévoiler

lacérer

chaque visage de l’abjection

tu t’acquitteras

à visage découvert

De la graine de lumière

dispensée à ton espèce

chue dans tes entrailles

tu te feras gardien et vestale

À ces conditions préalables

tu mériteras ton vrai nom

homme de parole

ou poète si l'on veut

Inédit, janvier 2006

4 Comments:

roughly (very):

The right to rebel you employ

brings

the obligation to distinguish

to unveil

to shred

each look of humiliation

redeemed

into a face unmasked

By the speck of light

bestowed on your kind

fallen in your gut

you are guardian, vestal

From these preliminary conditions

you earn your real name

man of speech

or poet if you prefer

Wow, great post. I enjoyed that.

I'd love to see a side by side comparison of the poetry written before and after being tortured...if he wrote any then. I mean, I can only imagine the difference in writing about that subject from his point of view. I think of Marianne Faithful....her cover of the Stones' As Tears Go By. The two versions, the one when she was young and bright and 60s pop type rock sound, and the other, years and years later, after she had been beaten to hell by heroin. Boy the sound of that latter version gives me chills...where her voice is just crawling over the lyrics like she wrote them herself, and unwillingly.

Glad this spoke to you.

Here's another (the rest is hidden behind a subscription wall):

O death of mine

By Abdellatif Laabi

Thirty-three years old

and death on my mind

Not death in the abstract

but my death

which may come at any time

and in the experiencing of it

accounts still to be settled

This is no bleak reflection

but realism

when prison is the future

and day and night

the torturers

dictate my fate

O death of mine

be gentle like those happy dreams

where I overcome all obstacles

and at maze end

grasp and caress my beloved’s hand

rediscover the colour of her eyes

and see the dew drop of a tear

cloud their (...)

He was born in 42, so this was either written in '75 in jail, or is lookingback to that time. Prison the future, fate in the hands of torturers. It may well be that for him it's easier to imagine the graphic images of “Glory to Those Who Torture Us”

than to later inscribe in graphic detail his own experience. But he doesn't pull back any emotional punch.

. . .death

which may come at any time

I may well pick up the Selected next time I'm in Berkeley.

Not to say graphic detail would be better. But writing from a feeling of empathy or imagination simply cannot stand next to one's own experience of something, to my thinking. Not to belittle his work at any time period, of course.

Post a Comment

<< Home