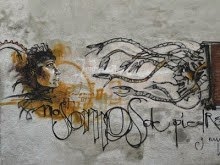

"all languages are multilingual"

12 native Peruvian languages in danger of disappearing~

During the last decades 30 of the 100 existing native languages in Peru are extinct and today 12 more are in danger of disappearing, warned James Roberts, director of Peru's Summer Institute of Linguistics.

"The decrease in native Peruvian languages is mainly due to the influence society has on the various ethnic groups living in rural areas and the fact that the population within each group is getting smaller", Roberts said. In ethnic groups with a population less than one thousand people, only the parents speak the native language because the children learn Spanish. "If authorities and parents continue to send their children down this educational path, it is likely that their linguistic identity will be lost after one or two generations", he warned.In addition to Quechua and Aymara, the common indigenous languages spoken mainly in the Peruvian Andes (departments of Cusco, Ancash, and Ayacucho), there are several other languages spoken in Peru's Amazon rain forest. Some non-quechua languages that could soon be extinct are Sharanahua, Yaninahua, Kashinahua, and Kapanahua in the department of Ucayali, as well as Orejón, Sequoia and Arabela spoken in Loreto.

45 percent of Peru's population is indigenous and 25 percent speaks a maternal language other than Spanish.(Source: La Republica)

Teaching overwhelmingly in English, as mandated by 1998's Proposition 227, has had no impact on how English learners are faring in California, a state-mandated study released Tuesday has found. The ballot measure, approved by 61 percent of the state's voters, promised that immigrant children and others who don't speak English at home would assimilate much faster if all their classes were taught in English. . . . About 8 percent of current California students are in bilingual programs, down from 27 percent before Proposition 227 went into effect in fall 1998. [San Francisco, CA - 02.22.06]

The Senate voted on Thursday to designate English as the national language. In a charged debate, Republican backers of the proposal, which was added to the Senate's immigration measure on a 63-to-34 vote, said that it was equivalent to establishing a formal national anthem or motto and that it would simply affirm the pre-eminence of English without overturning laws or rules on bilingualism. . . . the Senate also approved a weaker, less-binding alternative declaring English the "common and unifying" language of the nation, on a 58-to-39 vote. . . . Senator Harry Reid of Nevada, the Democratic leader, said the Inhofe amendment was racist. "Everybody who speaks with an accent knows that they need to learn English just as fast as they can," he said. [Washington, DC, 05.18.06]

Iowa Congressman Steve King finally hit paydirt. The Republican from Iowa has had little success getting his colleagues to sign onto bills of his that allow judges to carry firearms, or to spend $100 million on a fence along the U.S. border with Mexico, or to cut the salaries of United State Supreme Court justices. But he's found willing signatories to his bill that would mandate that English is the official language of the United States. [09.13.06]

One local county has already made the decision to make English it's official language for county documents and two Idaho candidates running for congress have taken a stance on the issue. . . Several parents in Canyon County say they're angry that when their children go to school the pledge is not only being said in English, it's being said in Spanish and French, too. "They can practice lots of different things in Spanish. I don't have a problem with them learning Spanish but the Pledge Of Allegiance is one of the things we should just leave to English only," said Fred Ellis, a concerned parent. . . . Canyon County commissioners have already . . . made English the official language on all county documents. As commissioner Robert Vasquez puts it, "This is America. We all speak English and we have for 220 years." [Boise, ID - 09.14.06]

A petition to ban illegal immigrants from living and working in Cape Coral is now in the hands of the Cape Coral City Council. . . . Taking a stand against illegal immigration is why Tony Maida and Mary Ann Redman founded the group called Americans Standing Tall. Monday night they presented a petition with more than 1000 signatures to the Cape Coral City Council. "My first thought was it had Archie Bunker written all over it," said councilmember Tim Day. The petition proposes the city council name English the official language of Cape Coral. [Cape Coral, FL - 09.19.06]

The Metro Council passed a significantly neutralized version of a an ordinance declaring English the official language of the city and mandating official city communication, at least some of it, be done in English. The passage was only preliminary, however — the legislative body must still vote on the measure two more times before it can become official . . . The substitute English-language legislation Crafton introduced would exempt Metro from having to communicate in English “when necessary to protect or promote public health, safety or welfare” or “except when required by federal law,” according to the language of the bill. The change was, in part, a reaction to a memorandum by the Metro Legal Department saying the bill could violate the U.S. Constitution and the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964. [Nashville, TN - 09.20.06]

Recall petitions need to be printed only in English, even when some voters are not proficient in the language, a federal appeals court ruled Tuesday.

The federal Voting Rights Act requires ballots and other government-produced election material to be published in other languages if more than 5% of the voters speak a different language. But in a case involving the Santa Ana Unified School District, the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled Tuesday that the requirement did not apply to recall petitions written and circulated by citizens. . . . The judges also said that translating recall petitions into different languages in a place such as Orange County, which has a large and diverse population, would be costly and have a "chilling effect on the petition process." Judge Stephen Reinhardt concurred with the majority opinion written by Judge William C. Canby Jr. but said Congress should change the law to include recall petitions under the Voting Rights Act. In a sharply worded dissent, Judge Harry Pregerson wrote, "English-only petitions would perpetuate the very injustice the Voting Rights Act seeks to eliminate" and said the majority interpreted the law too narrowly. [Los Angeles, CA - 09.20.06]

A bid by a town to ask voters to make English its official language has ended because the state's highest court refused to hear its case. The state [NJ] Supreme Court late Monday declined to hear a dispute over Bogota's plan to ask voters in November whether to name English the borough's official language. "Justice prevailed," said John Carbone, the attorney for Bergen County Clerk Kathleen Donovan, who contended the ballot question was improper because the town did not have the authority to designate an official language. Bogota Mayor Steve Lonegan, who spearheaded the referendum effort, said he was disappointed by the high court's decision. "I think it's an absolute disgrace," Lonegan said. "This is a real attack on America.". . . The English-language dispute began when Lonegan demanded that a McDonald's in the town remove a Spanish billboard and replace it with an English one. [Trenton, NJ - 09.26.06]Juliana Spahr:

First, some truisms:

All languages are multilingual, full of words and concepts from afar, developed by the language habits of different places constantly rubbing up against each other.

All poetries, thus, are multilingual.

Some poetries though are more aware of being multilingual than others.

Then some obvious observations, when one talks about the US and languages, it quickly becomes obvious that it is impossible to say anything coherent. The US does not have an "official" language. Over 176 languages are indigenous to the US, although many of these are extinct. And around 162 languages are spoken in the US. (All these numbers vary from source to source.) But the collection of words and syntaxes that gets called English has an unchallenged dominance. It is the defacto language of the US, the language most often used by the government. And the US’s consistent underfunding of language acquisition programs in its schools makes this unlikely to change any time soon.

Despite English’s assured status as the de facto language of the US, there regularly are groups of people who are prone to hysterical anxieties that English is at risk. In the 90s, for instance, an "English Only" movement got a lot of media coverage (although variations on English only have been around for some time and never seem to completely go away). This movement argues that English is at risk in the US and attempts to provoke legislative changes that will make English the "official" language of the US. English only advocates have had some success. English is the official language of a number of states, although most of these states still produce government documents in other languages. But still, a number of states remain officially bilingual.

I start with these truisms and observations because I am often told when outside the US that Americans only speak English. That is true of many Americans . . . but it is not true by any means of all Americans.

A similar sort of contradiction in action is true of US literatures. While it is true that most of the classes in "American literature" and most of the anthologies that define "American literature" present only work written in English, the US has a long tradition of literatures written in other languages. And, as all places, a lot of literatures that mix different languages.

So, by way of introduction to the US poetries that lie outside of the "English only" mainstream, I want to make a somewhat false distinction. I want to claim that there are two forms of multilingual writing in the US: a multilingualism that uses the languages of empire and a multilingualism that uses at risk or marginal languages. . . .

That other multilingualism of US poetry, poetry that uses at risk or marginal languages, is a somewhat more specific project, one that is frequently rooted in identity. In this tradition, the poet writes in English but includes the languages of their immigrant or indigenous history. Much of this work tends to be explicitly political and uses clear and conventional language despite its multilingualism. . . .

The Chicano poet Alurista is frequently credited with beginning this tradition. He writes in Spanish and English starting in the 60s (and this is another one of those moments where US language politics gets complicated; Spanish and English are both colonial languages in the Americas but because of the Mexican-American war and the always complicated relationship between Mexico and the US at the border, the Spanishes of the Americas have marginal—although not really at risk—histories in the US and are often seen as second class languages; thus these Spanishes have their own movement of "linguistic independence" in the US).

While work written in English with Spanish is by far the most represented combination of languages in this multilingualism of at risk or marginal languages, there is an emerging tendency to use indigenous languages. Hawaiian sovereignty activist, poet, and essayist Haunani-Kay Trask, for instance, writes an English that includes Hawaiian in her Night is a Sharkskin Drum. She is notorious for the political intensity of her work which frequently criticizes the cliché of Hawai‘i as a multicultural paradise full of racial equality and points out that how Hawai‘i is still a colonized nation. The inclusion of Hawaiian is clearly presented as a political gesture. And Trask takes great pains to keep her work clear and accessible admist the multilingualism. Hawaiian words are prominently italicized and Night is a Sharkskin Drum has a seven page glossary at the back. There is little interest in the ambiguity or crosslingual punning that so defines the multilingualism of the languages of empire. Some other writers who do this sort of work are Robert Sullivan (a Maori writer currently writing in Hawai‘i) who mixes Maori and Englishin Star Waka and Teresia Kieuea Teaiwa (a writer of African-American and Kirabati descent with multiple Pacific affiliations who is currently writing in Aotearoa/New Zealand) who uses English and Gilbertese in parts of Searching for Nei Nim‘anoa.Now that I’ve set up these categories, I of course immediately should point out how they do not work all the time. Some of the most provocative multilingual work is happening outside of these categories. Rodrigo Toscano and Edwin Torres are two interesting examples of writers who do not fit well. Both mix an American Spanish into their English. Both are born in the US; Toscano is of Mexican heritage and Torres of Puerto Rican. So both use the language of their heritage identity, as do many of the writers of a multilingualism of at risk or marginal languages. But the work they write is way more disjunctive, arrhythmic, syntactically unusual than most of this work tends to be. And they both avoid the direct statement that characterizes the marginalized or at risk multilingualism.

James Thomas Stevens and Rosmarie Waldrop are two other exceptions to these two categories. Both write interestingly similar books in the 90s that mix Narragansett among their English. Stevens, the author of Tokenish, is a Mohawk poet. His turn to Narragansett could be read as a turn to a heritage language in that it is another indigenous language but when it comes down to it, that is probably not a fair reading of this complicated move. Waldrop, author of A Key into the Language of America, is a German immigrant to the US. Both write poems that are more in the disjunctive, arrhythmic, syntactically off than in the clear, political speech tradition. Both works are, I think, indicative of how complicated language choices can be for US poets, how full of multiple alliances. . . .Undeniably, though, a lot of US poetries in the last half of the twentieth and the beginning of the twenty first century are refusing to translate. My guess is that this refusal to translate has a lot to do with reactionary English only movements. Although English Only itself did not manage to make English the official language of the US, this movement was part of a larger anti-immigration sentiment that did have and continues to have some success in restricting immigration. As I write this large amounts of people, mainly in the west near the border with Mexico, are protesting various proposals before congress right now to arrest illegal immigrants and to further fortify the US/Mexico border. Just as it is impossible to read the multilingualism of modernism as at all separate from imperialism, I also think it is impossible not to read the multilingualism of contemporary US poetries as divorced from the language debates of the 90s. Multilingual word play in US poetries is a formal device that is unusually loaded with politics right now. It seems as if it can never avoid argument because merely to include another language in one’s work, any other language, is a pointed statement in the time of English only politics. But also, I see the proliferation in multilingual poetries, in addition to the obvious mimetic claims that some poets make, as indicative of how US poets are beginning to ponder more on the difficult role that US cultural products play in globalization. Stevens’s and Waldrop’s turns to the dead language of Narragansett in their works (no mimesis there) reads less to me as a desire to preserve Narragansett and more as a desire to think about how clearly the last thirty or so years have demonstrated the close ties between the English language and globalization.

1 Comments:

This is really interesting. Scholarship has a weird way of adding to the extinction of languages: many historians only learn the ancient dialects to do work but never bother with modern translation and literature. Indigenous languages are already looked at as 'dead' languages like Latin as oppose to the older forms of a language that still exists today (like comparing older forms of english lit.)

Post a Comment

<< Home