" . . . I bring 45 years of life to those canvases. I bring a tremendous amount of joy to those canvases, I bring a tremendous amount of freedom to those canvases, I bring a tremendous amount of anger . . . "

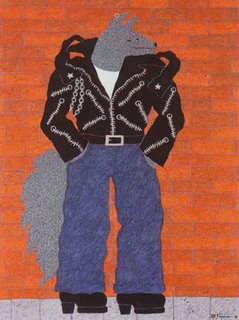

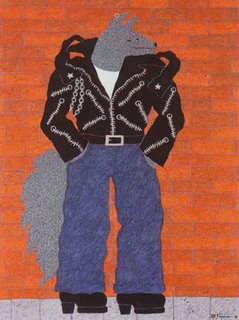

"When Coyote Leaves The Reservation (a portrait of the artist as a young Coyote)"". . . the most profound political statement being made today is by any Native American that is still breathing"

"When Coyote Leaves The Reservation (a portrait of the artist as a young Coyote)"". . . the most profound political statement being made today is by any Native American that is still breathing"

Another great, creative soul has moved on—leaving us with a substantial body of work to contemplate, enjoy, absorb. I heard the news on KPFA; the Sacramento Bee didn't take notice, unlike the Albuquerque Journal. Harry Fonseca was born 60 years ago today in Sacramento, CA of Nisenan Maidu, Hawaiian, and Portuguese heritage & studied at Sac State with noted Native American (Wintun) artist/poet/teacher/dancer Frank LaPena (Tauhindauli), "but was reluctant to become an academic stylist, so he decided not to continue formal art education in order to pursue his own vision . . . In his close to twenty-year career as an exhibiting artist, Harry Fonseca's work has gone through a number of transformations, but the one constant has been his openness to new influences and sources of inspiration. " (see the bio on his webpage)

His work draws on Native American artistic traditions and imagery in dialogue with abstract expressionism, pop art, west coast figurative and abstract landscape painting, as well as other artistic trends from around the globe. I became aware of his painting sometime in the mid-80's, a period when I was reading some Native American mythology and exploring the pictographs & petropglyphs of the west, visiting sites in California, Nevada, Utah, British Columbia, and Baja. Fonseca's paintings struck an immediate chord. Here was someone working with this ancient imagery and mythology, utilizing it in a thoroughly contemporary idiom, and grappling with issues of identity, assimilation, diversity, tradition, and contemporary culture.

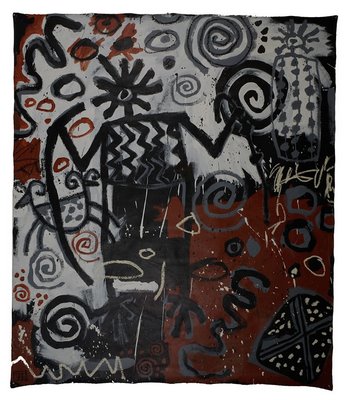

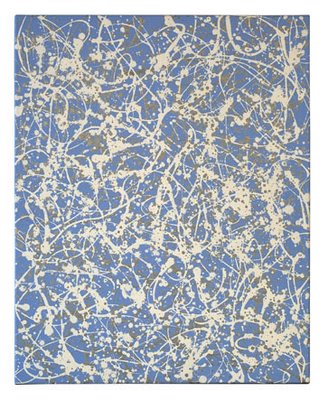

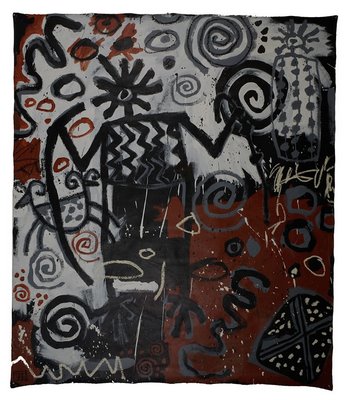

"Stone Poem #1" (1989, 60"x 72")

"Stone Poem #1" (1989, 60"x 72")

In an interview ten-some years ago with Larry Abbott, he recalls how:

. . . in terms of art education, I started in high school, but probably more important than doing actual painting—I remember painting with oils and how awkward that was, painting sail boats and that kind of thing—was the teacher I had. He would show us slides because he was educated in Italy, so he had tons of slides of the Renaissance. That was a really stimulating time to see all these images, so-called "fine art." Then, by the time I got to college, Abstract Expressionism was still popular, and I remember Robert Motherwell, seeing some of his work. I fell in love with that and started to really move paint around and drip paint and have a great time. But not really with any direction. It was almost art for art's sake.

The paint was just a going and a going. Then, I found out more about my Native American background, and became involved with the dances and the whole traditional base. That really gave me a foundation, not only for me but for my art work as well. It's still here. It's still very, very strong. It has a great deal of meaning to me, even when I am not doing a petroglyph, or a coyote or something, there's still something there.

LA: Some of your early work was based on basketry designs.

HF: I think at that time it wasn't even so much the painting. It was just the whole process of living . . . being involved with the Native American community . . . talking to Henry Azbill . . . talking to Frank Day . . . being taught by Frank LaPena . . . going up to the dances at Grindstone . . . being asked to dance with the Maidu dancers. Being initiated as a dancer was just a knockout! Life just went on . . . pot luck picnics and all of that stuff was involved. It's, I don't know, just very strange. The Santa Fe art scene, I'm not sure what it is. It's strong, but it's not the experience I had in Northern California. Of course, there is a very strong Pueblo connection to the art here. So, I'm in a foreign world in a way, but I like this world, too.

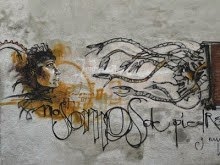

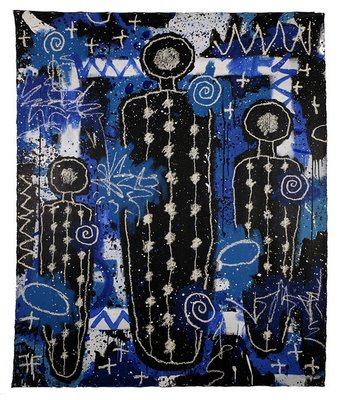

"Maidu Creation Story" (1999)

from the bio:

. . . the creation myth of his people, as recounted by his uncle, Henry Azbill, became the source of a major 1977 work, Creation Story. This piece visually embodies the underpinnings of Maidu culture. . . . This myth continues to inspire Fonseca, as his 1991 The Maidu Creation Story shows. The basic imagery of this painting recalls petroglyphic symbols, and although less figurative than the 1979 work, still seeks to give visual form to myth. Fonseca does not replicate his past imagery but looks for new ways of connecting to tradition. Regarding the 1991 work, Darryl Wilson has pointed out that Fonseca "was particularly struck by ancient rock art from the Coso Range in the high desert country near Owens Lake [north of Ridgecrest, California, 'protected' by the U.S. Navy]. Because of its powerful appeal, he incorporated some of its images into the similarly powerful and appealing creation story Henry Azbill told him."

. . .

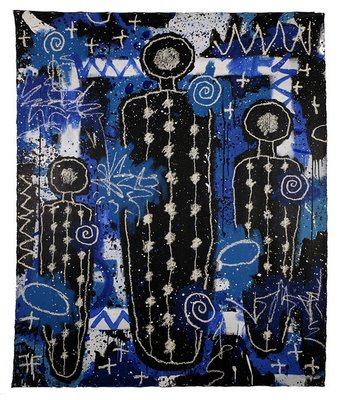

Fonseca's continuing interest in rock art led him to develop the Stone Poems, an extensive series of works exploring the imagery of petroglyphs, not only from California but throughout the West and Southwest, especially Utah. The Stone Poems are not meant to be so much an interpretive recording of rock images but a way of self-exploration. The canvases, some as large as 6' by 12', suggest the size and scope of petroglyphic panels in situ.

He returned again to the creation myth in the 1999 painting shown above, and often used

Coso imagery in his paintings, prominently here in the anthropomorphs of this painting also from the

Stone Poem series:

"Nocturne #12" (1990)

"Nocturne #12" (1990) Fonseca is probably best known for his many depictions of Coyote—dancing in traditional regalia or on an opera's proscenium stage, decked out in leathers or as an exotic movie star, hanging out in the painted desert, juggling, skateboarding in SoCal, or shufflin' off to Buffalo in an Uncle Sam suit—a mythologic presence negotiating and slyly confronting American culture.

Another level of transformation is evident in the Coyote series, which Fonseca began in 1979 (and which, after a few years' hiatus, he has started again). The subject of these works is Coyote, the trickster and transformer. Fonseca resituates the culture hero into contemporary settings, such as San Francisco's Mission District. Coyote can become an updated and sneaker-wearing Rousseau, holding his palette on a Parisian quay (Rousseau Revisited, 1986), or headress-clad and sneakered (Coyote in Front of Studio, 1983). Coyote becomes an alembic through which Fonseca filters his vision of the artist, and the Indian, in society. (bio)

Gary Snyder, in the "Forward" to The Maidu Indian Myths and Stories of Hanc'byjim (William Shipley, ed. & trans., Heyday, 1991), notes that after winning a "gamble" with Earthmaker as to whether there should be death or reincarnation ("When anyone is dead, / why should he come to be walking around again?"), it is Coyote in the creation story who "goes on to finish defining the world which is our present reality."

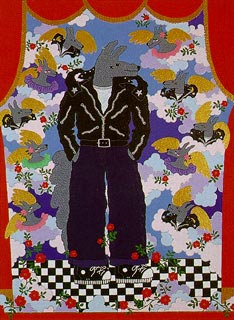

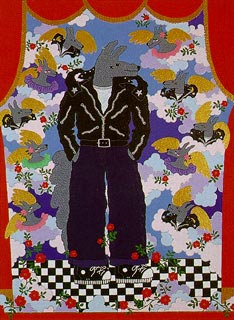

"St Coyote" (1993)

"St Coyote" (1993)

Fonseca, in the interview, talking about his St Coyote painting:

Well, that same coyote image is not a new image; I've done that in the past. What brought this about is, I had heard that the Catholic Church wanted to make Father Serra a saint and I just couldn't believe it. Then, the Native America community got involved in Southern California to protest his canonization. I don't know where it is at this point, but there was a commercial for tuna fish that said, "Sorry, Charlie, only the best tuna will do," or something. So, the original title of this Saint Coyote piece was Sorry, Father Serra, Only the Best Coyotes Will Do. Then, I turned it into Saint Coyote to make it a little cooler. I thought if anybody is going to get to sainthood, it's going to be coyote before Father Serra. It's also a play on the Renaissance with all the angels, and the Baroque period with everything moving around and those checkered floors. It's a fun piece.

from the bio again:

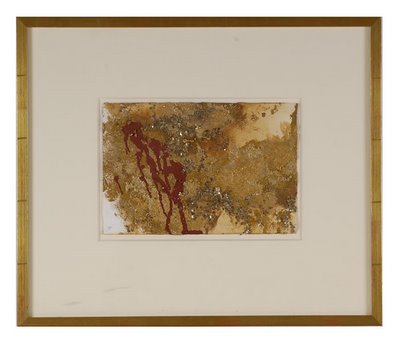

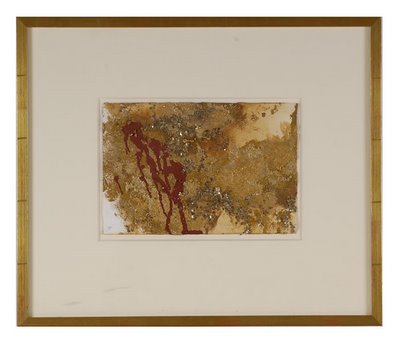

Fonseca's work took a more political turn with the 1992 Discovery of Gold and Souls in California series. Each of these small mixed-media pieces, measuring about 15" x 11", offer subtle variations on the image of a black cross surrounded by gold leaf and partially covered with red oxide. Fonseca has stated that this series "is a direct reference to the physical, emotional and spiritual genocide of the native people of California. With the rise of the mission system, and much later the discovery of gold in California, the native world was fractured, and with it, a way of life and order devastated."

"Discovery of Gold and Souls in California #28" (1992)

"Discovery of Gold and Souls in California #28" (1992)An insistent image of the artist's hand overlying the palimpsest of paint, layered history, a present-day echo of the ubiquitous hand-print found at rock art sites around the planet?

from the interview:

Again, I don't know the reason for them coming about, but I know how they came about. I was moving here to New Mexico. I'd put away everything but I wanted to paint, so I had some black paint, red oxide and some gold leaf, artificial gold leaf around, so I started to do the series. I did four of the crosses and then I thought, well, I don't know if I want to continue these because they were so brutal. I did four of them and called them The Discovery of Gold and Souls in California. There was something that intrigued me about the brutality but also the elegance of them, so I ended up doing 160, and I think that they probably are my most pointed political statements. That doesn't mean a great deal to me. I mean, I don't think you have to toss a bomb at something that you dislike to be conscious of political situation. I don't know if I told you this before, but I think the most profound political statement being made today is by any Native American that is still breathing. They don't have to be marching, you know, just breathing—they don't have to be doing anything. That's the perception that I have and so I don't need the drama in some political way. I would rather create drama in other ways.

The gold rush took place in the heart of Nisenan territory, already under siege by anglo settlers. "Between 1846 and 1870 alone, the number of California Indians declined from 150,000 to 30,000, an 80 percent reduction in population. They died from disease, starvation, forced labor, and state-sanctioned murder. Historian James Rawls refers to this event as 'California's Holocaust.'" Fonseca's Portugese heritage is due to the large numbers of immigrants from the Azores to the central valley; his Hawaiian side is the result of John Sutter's having "brought in 1939 10 Native Hawaiians to California, among them Fonseca's ancestors Ioane Ke'a'a'la O Ka'iana and Sam Kapu. Sutter's reliance on these Native Hawaiians and local Nisenan Maidu to build his fort and empire is not to be underestimated." (There's a small State Indian museum today outside the walls of Sutter's Fort State Historic Park; Discovery Park, at the junction of the American River with the Sacramento, sits on what was once a Nisenan village).

Visiting his sister in 1997 at the Shingle Springs Rancheria (160 acres, no mule), in the lower foothills about 10 miles from Coloma, site of another Nisenan village (& another SHP, Marshall Gold Discovery) where the valuable glittery stuff was famously found, Fonseca began a stunning new series, The Discovery of Gold in California, which are more intensely personal, abstract paintings.

"The Discovery of gold in California #35" (1997)

Being in the environment in that country, feeling the energy of the land, gave me a chance to work with the subject matter on a different level than before . . . The upheaval that took place on all levels was the catalyst for this body of work. It started with the land and Native American cultures that were disrupted if not destroyed, and evolved into how the Gold Rush affected everybody. The drama just grew and grew.

A healthy selection from this series (300 in number) can be viewed at the Oakland Museum's on-line gallery: The Discovery of Gold in California, from which the unattributed text & quotes above were taken.

Harry Fonseca: Earth, Wind, and Fire (1996. Essays by Elizabeth Woody, Margaret Archuleta, and Floyd Solomon. Trim size 9 x 9 inches; 40 pages; 10 color and 10 black-and-white illustrations) is out of print, but available as a pdf file.

& don't miss the galleries at The Fonseca Studio (click on "StudioWork")

The connections made in my work are not exclusively cultural. Myth and history comprise the thematic elements of my art. My paintings incorporate simple forms, basic color and design, and abstract landscape. Ancient symbols are rendered as contemporary and relevant without losing the past. In a passionate confrontation with this subject matter, images unfold and hint at the creative process itself. Mythology, transformed into a sense of myth, reveals its drama, its magic, its presence and life.

As an artist with 43 years of work, my art continues to grow and change. This growth and its process reveals the many cultures and the universal artistic exploration of passion, struggle and fight, and its subsequent transformation into art. (Growth and the Creative Process: 43 Years of Work, Harry Fonseca)

Thank you, Harry; your work continues to dance.