Nathaniel Mackey: "the work-in-progress we continue to be"

(from "Song of the Andoumboulou 16: cante moro," Whatsaid Serif, City Lights, 1998)

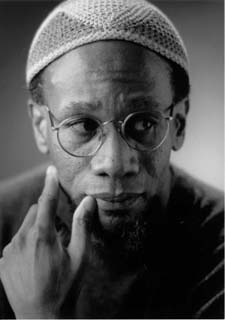

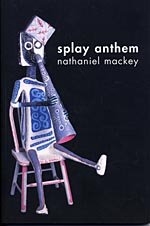

Last week the National book awards announced that Nathaniel Mackey is one of this year's poetry finalists for his latest book, Splay Anthem (New Directions, 2006). Quite a long journey to the A-list tier of independent publishing from the self-published chapbooks Four For Trane (Golemics, 1978) and Septet For The End Of Time (Boneset, 1983), gathered in his first full-length collection Eroding Witness (U of Illinois, 1985).

This well deserved recognition outside the insular world of contemporary avant garde poetry follows a recent article on Mackey in The Nation by John Palattella, "Poetry, From Noun to Verb" (there is a nice bio early in the piece). He notes of the "Septet" series that "The circumstances are hardly tranquil. The section's title alludes to the 'Quartet for the End of Time,' written by the French composer Olivier Messiaen in 1941 in a prisoner-of-war camp, and in each poem a persona drifts into fragmentary recollections of his or her past after waking up into, rather than out of, horrifying dreams. But the personae aren't necessarily trapped in a nightmare from which they never awake. Instead, they are simultaneously constrained by history and compelled by musical powers to test its limits. . . . The overall outlook of the series, however, is not apocalyptic but Sisyphean: Loss is inexorable, and the test is how one manages to endure it."

Bittersweet kissSweet bitter, Anne Carson tells us, would be the literal translation of Sappho's epithet for eros, driving throughout Mackey's work an elaborate, nuanced poetics of loss and becoming, longing and desire. Two open-ended serial poems twine throughout his four full-length poetry collections. One, "Mu," echoes the title of two 1969 Don Cherry/Ed Blackwell live duet recordings: "numbed / inarticulate / tongues touching / down on love's endlessly / warmed-over thigh" (from "Irritable Mystic - 'mu' fifth part").

of this my tightlipped muse, puckered

skin of the earth as though

its orbit

shrunk.

Shrill hiss of the sun so

much a doomsday prophet gasping voiceless,

asking,

When will all the killing

stop?

As though the answer were not so visibly

Never.

As though the light were not all but

drowned in the Well to the uncharted

East I sought...

(from "The Phantom Light of All Our Day," Eroding Witness)

The opening syllable in music, "mu" conjures "the Greek form of muthos," "myth and mouth," "also lingual and erotic allure, mouth and muse, mouth not only noun but verb and muse likewise, lingual and imaginal process, prod and process. It promises verbal and romantic enhancement, graduation to an altered state, momentary thrall translated into myth. . . . carries a theme of utopic reverie, a theme of lost ground and elegiac allure recalling the Atlantis-like continent Mu . . . Any longingly imagined, mourned or remembered place, time, state, or condition can be called 'Mu'" ("Preface" to Splay Anthem).

Its sense even splays to include the Papua New Guinea Kaluli's myth of poetry & music's "origin & essence," the cry of the boy turned into a muni bird. The new book opens with "Andoumboulus Brush—'mu' fifteenth part—":

He turned his head,"Song of the Andoumboulou" also takes its title from a musical recording of Dogon music from Mali, and refers to mythological ancestors in the villagers' cosmology who are "not simply a failed, or flawed, earlier form of human being" but also "the work-in-progress we continue to be":

spoke to my clavicle,

whispered more than

spoke. Sprung bone

the

obtuse flute he'd

long wanted, blew

across the end of it

sticking

up... Blew across its

opening. Blew as if

cooling soup... Someone

behind him blowing

bigger

than him giggled,

muse whose jutting

lips he kissed as he

could... "Mouth that

moved my mouth,"

he

soughed, hummed it,

made it buzz... Hummed,

hoped glass would break,

walls fall. Sang thru

the

cracks a croaking

song

to end all song,

tongue's tip seeking

the gap between her

teeth, mouth whose

toothy pout made

"mu"

tear

loose

Francis Di Dio, in the liner notes to Les Dogon, his 1956 recording of Dogon music for Disques Ocora says the song of the Andoumboulou is addressed to the spirits. Part of the Dogon funeral rites, it begins with sticks marking time on a drum's head, joined in short order by a lone laconic voice gravelly, raspy, reluctant—recounting the creatioon of the world and the advent of human life. Other voices, likewise reticent, join in, eventually build into song, a scratchy, low-key chorus. Song subsided, another lone voice eulogizes the deceased, reciting his genealogy, bestowing praise, listing all the places where he set foot while alive, a spiral around the surrounding countryside. Antelope-horn trumpets blast and bleat when the listening ends, marking the entry of the deceased into the other life, evoking, Di Dio writes, "the wail of a new-born child, born into a terrifying world."from "On Antiphon Island—'mu' twenty-eighth part— :

. . . The poems' we, a lost tribe of sorts, a band of nervous travelers, know nothing if not locality's discontent, ground gone under. Sonic semblance's age-old promise, rhyme's reason, the consolation they seek in song, accents of transit. . . . Glamorizations by the tourist industry notwithstanding, travel and migration for the vast majority of people have been and continue to be unhappy if not catastrophic occurrences brought about by unhappy if not catastrophic events: the Middle Passage, the Spanish Expulsion, the Irish Potato Famine, conscripted military service, indentured labor systems, pursuit of asylum. . . .

("Preface" to Splay Anthem)

Where weIn an Introduction to his first volume of essays, Discrepant Engagement: Dissonance, Cross-Culturality, and Experimental Writing (Cambridge, 1993), Mackey writes:

were was the hold of a ship we were

caught

in. Soaked wood kept us afloat... It

wasn't limbo we were in albeit we

limbo'd our way there. Where we

were was what we meant by "mu."

Where

we were was real, reminiscent

arrest we resisted, bodies briefly

had,

held on

to

The title of this book . . . is an expression coined in reference to practices that, in the interest of opening presumably closed orders of identity and signification, accent fissure, fracture, incongruity, the rickety, imperfect fit between word and world. Such practices highlight - indeed inhabit - discrepancy, engage rather than seek to ignore it. Recalling the derivation of the word discrepant from a root meaning "to rattle, creak," I relate discrepant engagement to the name the Dogon of West Africa give their weaving block, the base on which the loom they weave upon sits. They call it the "creaking of the word." It is the noise upon which the word is based, the discrepant foundation of all coherence and articulation, of the purchase upon the world fabrication affords. Discrepant engagement, rather than suppressing or seeking to silence that noise, acknowledges it. In its anti-foundational acknowledgment of founding noise, discrepant engagement sings "base," voicing reminders of the axiomatic exclusions upon which positings of identity and meaning depend.Paul Naylor begins his essay, "The 'Mired Sublime' of Nathaniel Mackey's Song of the Andoumboulou" with a 1981 quote from the Martinican poet, Édouard Glissant (who also provides one of Splay Anthem's two epigraphs):

. . .

Discrepant engagement, rather than suppressing resonance, dissonance, noise, seeks to remain open to them. Its admission of resonances contends with resolution. It worries resolute identity and demarcation, resolute boundary lines, resolute definition, obeying a vibrational rather than a corpuscular sense of being, "a quality," as [Clarence] Major puts it, "of which sharp contact is / the qualification, a remarkable verb quiver." To see being as verb rather than noun is to be at odds with hypostasis, the reification of fixed identities that has been the bane of socially marginalized groups. It is to be at odds with taxonomies and categorizations that obscure the fact of heterogeneity and mix. [The essay] "Poseidon (Dub Version)" brings discrepant engagement to bear upon questions of representation, naming, and identity in a context of cultural mix inherited from colonizing projects, arguing that it dispels or seeks to dispel the specter of inauthenticity that haunts post-colonial hybridity, dislodges or seeks to dislodge homogeneous models of identity and assumptions of monolithic form. But, as I have already indicated and by titling the book as I have, discrepant engagement is relevant not only to writers from recently decolonized regions such as [Wilson] Harris and [Edward Kamau] Brathwaite. It pertains to and is symptomatic of a postmodern/postcolonial suspicion of totalizing paradigms . . .

"We are aware of the fact that the changes of our present history are the unseen moments of a massive transformation in civilization, which is the passage from the all-encompassing world of cultural Sameness, effectively imposed by the West, to a pattern of fragmented Diversity, achieved in a no less creative way by the peoples who have today seized their rightful place in the world."

Fray was the name where we cameNaylor:

to next. Might've been a place,

might not've been a place but

we were there, came to it

sooner

than we could see... Come to

so soon, it was a name we stuck

pins in hoping we'd stay. Stray

was all we ended up with. Spar

was another name we heard

it

went by... Rasp we also heard it

was

called... Came to it sooner

than we could see but soon enough

saw we were there. Some who'd

come before us called it Bray...

(from "Song of the Andoumboulou: 50")

Discrepant engagement, then, not only denotes a theory of cross-culturality; it enacts one in the structure of its definition. The crossing traditions of Dogon and Western cosmologies and philosophies of language allow Mackey to present a second crossing, one in which traditions of sense and nonsense, noise and word, encounter one and other. Mackey uncovers in this second opposition the cross-cultural moment shared by both traditions, although the judgment concerning that moment's value is clearly not shared. This opposition animates most of Mackey's writing and generates the cross-cultural recognition embodied in the moment of song. . . . For Mackey, the cultural judgment concerning the value of song coincides with the way a given culture reacts to the opposition between noise and word, with how much "creaking" a culture tolerates in its words. If we recall Mackey's contention that the "founding noise" of language also serves to remind us of a tradition's "axiomatic exclusions," then it follows that a culture's definitions of and judgments about noise have political as well as aesthetic implications.Or in the words of the fictional Aunt Nancy in his first novel, Bedouin Hornbook:

". . . the culture you're calling 'whole' has yet to assume itself to be so except at the expense of a whole lot of other folks, except by presuming that what they were up to could be ignored at no great loss . . . What makes you feel excluded by our sources if not the exclusionistic biases of the culture you identify as 'whole' boomeranging back at you? . . . You may want something different, something more modest maybe, but your modesty betrays its falseness, shows itself to be the wolf-in-sheep's-clothing it is, when you saddle up your high horse to tell the rest of us we have to likewise lower our sights."

Palattella:

Mackey is equally sensitive to how the history of the diaspora has been cheapened. In an essay on the Guyanese novelist Wilson Harris, a writer second only to Robert Duncan in Mackey's personal canon, Mackey writes that it is "customary to speak of the West Indies almost wholly in terms of cultural deprivation or cultural parasitism." Following Harris, Mackey notes that the novels of V.S. Naipaul epitomize this tendency by judging the West Indies according to European cultural standards. Naipaul clings to the conventions of European fiction to insulate himself against the islands' "conventionlessness." Harris, on the other hand, writes about the West Indies in a way that avoids "imprison[ing] it in its deprivations." "The insularity of the various African peoples brought to the New World," Mackey argues, "was broken or dislocated by the Middle Passage. Harris views this breakage, this amputation, as fortunate, an opportune disinheritance or partial eclipse of tribal memory that called creative forces and imaginative freedoms into play."from "Song of the Andoumboulou 16: cante moro," (Whatsaid Serif, City Lights, 1998):

. . . In The Odyssey the wandering Odysseus returns home because of his ability to respond to circumstances that continually change. In the epic of the Andoumboulou poems, the only dwelling the wandering tribe can hope to inhabit is amid continuous change.

As Mackey knows, to write such an epic is to risk cultivating a macabre obsession with wounds, a habit that is all too common, whether it's Oprah touring Auschwitz or a literary theorist fixated on trauma. In "Gassire's Lute," a book-length essay on Duncan's Vietnam War poems based on his dissertation, Mackey notes that Duncan walks a tightrope between "humanist outrage and a cosmologizing acceptance of war.... The outrage has to do with the suffering of actual men and women and the cosmology, the poetics, with our being other than the suffering part of ourselves." Throughout the Andoumboulou poems Mackey walks a similar tightrope, one stretched between the poles of humanist outrage and a cosmologizing acceptance of the diaspora. He favors neither pole, instead spending most of his time at the tightrope's midway point.

tightand later in "Song of the Andoumboulou: 58":

flamenco strings

distraught...

Some

ecstatic elsewhere's

advocacy strummed,

unsung, lost inside

the oud's complaint . . .

The same cry taken

up in Cairo, Cordoba,

north

Red Sea near Nagfa,

Muharraq, necks cut

with the edge

of a

broken cup...

Rummaged around on all fours toIt's a tough, insistent lyricism, a poetry that aspires, like the Dreamtime, the altjeringa, of Australia's Aranda, to also be "an awakening to rather from dream . . . a way of challenging reality, a sense in which to dream is not to dream but to replace wakening with realization, an on-going process of testing or contesting reality, subjecting it to change or a demand for change" ("Preface," Splay Anthem). In a paper delivered at a 1990 Poetry Project panel, Poetry for the Next Society, Mackey asks: "What basis do we have for believing that poetry's marginality in this society will end in any near future? In what sense can we speak of "poetry for the next society"? My sense of it is that for quite a while poetry will continue to be against the society and we would need to talk about what kinds of changes would have to take place for that to not be the case." He concludes:

bug accompaniment. What we wanted

we couldn't have. Multiple the

names it went by, legion, wars

over

which one fit broke out, nation of

none though we were... Not yet

nation of Nub that we were, said to've

been born with barbs in our skin,

anaesthetic nation of Nuh... Said

to've

been born in beds made of glass,

"Bed,

be our balafon bridge," we exhorted,

"bed, be our rhythm log."

[...]

. . . We were never all there. Raw knuckles

pounding the dirt bled rivers. Bloodrun

carried

us away

So, what kind of society will the next society be? And what are the implications of that for poetics? It doesn't seem that you can answer the one question without answering or trying to answer the other. . . . I'd like to . . . remind us of Reverend David Garcia's pointing out that the word ecclesiastes means a "calling out," and think about the way in which several times during the symposium we've had people lament the loss of ritual, meaning, myth and the sorts of things that can make for a collective calling out and coming to one another. We have to ask will there be a society that we can be for and, if so, what kind of society that would be. I kept thinking of Robert Duncan's line "would-be shaman of no tribe I know." I wonder what kind of tribe we're going to bring about in the next society.One whose dreamers, fully awakened to our current nightmare, "the imperial, flailing republic of Nub the United States has become, the shrunken place the earth has become, planet of Nub" ("Preface" to Splay Anthem), find themselves members of (as in the book's final poem, "Song of the Andoumboulou: 60") a ". . . first unfallen church of what might've / been. Let run its course it would have / gone otherwise, time's ulterior bequest . . .":

Day late so all the old attunements gave_______________________________________

way, late but soon come even so... A

political trek we'd have said it was

albeit politics kept us at bay, nothing

wasn't

politics we'd say. Wanting our want to

be called otherwise, kept at bay though

we were, day late but all the old stories

echoed

yet again, old but even so soon come... A

mystic march they'd have said it was,

acknowledging politics kept us at

bay, everything was mystical

they'd say. Wanting our want to be

so

named, kept at bay as we were,

what

the matter was wasn't a question, no

ques-

tion what

it was.

poems online:

Academy of American Poets (3 poems)

"Song of the Andoumboulou: 48" [pdf]

On Antiphon Island—"mu" twenty-eighth part—

Groove Digit (poems, prose, interviews, essays about)

audio online:

PennSound

U of Chicago: reading & lecture

Somehow in his busy schedule, this man finds time to do a two hour radio program, Tanganyika Strut. The playlists show the musical range he covers: Andalusia to Africa, american jazz, Brazilian, Caribbean, and south Asian musics. The programs aren't archived, but can be heard Sundays, 3:00 - 5:00 PST, via a live stream.

Good luck with the award, Nate.